| ALL |

|

NEW DELHI, INDIA

| OVERVIEW |

|

| |

At his Delhi coronation ceremony in 1911, King George V of Great Britain made a surprise announcement—the transfer of the Indian capital from Calcutta (the seat of British power for over a century) to Delhi. The British had been considering a more central administrative capital as early as 1857 when revolts throughout northern India shook their control. Delhi's strategic north-central location, where the ancient Grand Trunk Road and the navigable Yamuna River come together, made it a logical choice. The fact that it was cooler and less polluted than Calcutta certainly helped as well. The site had been home to at least a dozen different cities over the previous three millennia and served as the capital for over six centuries during the rule of the Hindu Rajputs, the Delhi Sultanates, and the Mughals.

After the announcement, the Delhi Town Planning Committee was immediately established, whereas the selection of the principal architect was a more contentious affair. British architect Edwin Lutyens (1869-1944) was awarded the prestigious project to design the imperial city, more for his political connections than for his professional experience. The British Viceroy had preferred architect Herbert Baker (1862-1946), who was asked to collaborate.

At the time, half of the native population of 233,000 lived in the crowded city of Shahjahanabad (founded in 1648 by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan), in an area of about four square kilometers. The Committee searched for a location at a respectable distance from the Indian city but close enough that they would be able to make their presence felt. They ultimately selected a site on Raisina Hill some 5 kilometers southwest of the native city, between a high ridge and the Yamuna River. The new city would accommodate over 50,000 residents on an area of 26 square kilometers and would have provisions for future expansion.

The team of Lutyens and Baker organized the layout of the city in the tradition of the City Beautiful, a stylistic movement with roots in 19th-century France. The style was then becoming fashionable for large civic projects throughout the world and was particularly popular in colonial capitals because it conveys with ease a sense of both dominance and exclusivity, two important constructs to maintain when controlling alien regions. The plan for New Delhi incorporated all the basic tenets of City Beautiful design, including large-scale Beaux-Arts architectural elements, grand boulevards, and an abundance of gardens, parks, fountains, and sculpture.

The apex of Raisina Hill was blasted to create an artificial plateau above the old city. Atop this plateau were located the most important buildings of the British Raj: the Viceroy's House (1929, now Rashtrapati Bhavan) and the Secretariat Blocks (1928). Despite its solid horizontal massing (measuring 189 by 158 meters), the Viceroy's House appears monumental, given its hilltop location and a dome that rises 35 meters above the ground. Designed by Lutyens, the Viceroy's House contains several grand halls and courtyards, including the famous circular throne room under the dome for the Viceroy and his wife (presently Durbar Hall, used for ceremonial occasions). The gardens on the west side of the Viceroy's House were laid out in the Mughal tradition of four squares with watercourses and fountains. The Secretariat Blocks, designed by Baker, are identical oblong classical structures on the east side of the Viceroy's House and today house the offices of the various government ministries. The Viceroy's court and the courts of the two secretariat blocks create a grand urban space known as the Government Court. This space is further defined by the Jaipur Column (1931), a gift of the Maharaja of Jaipur, and the Dominion Columns (1931), gifts from the other great dominions within the British Empire.

From this commanding acropolis, the team laid out the processional avenue Kingsway (presently Rajpath) running between the Secretariat Blocks and east for 3 kilometers; it was lined by canals and fountains for its entire length. At the terminus, Lutyens designed the monumental All-India War Memorial Arch, popularly called India Gate (1931), which, located at the center of five radiating axes, recalls Paris's Arc de Triomphe. The Palladian-style India Gate is 43 meters high and commemorates the Indian and British soldiers who died in three wars, including World War I. Facing it is a sandstone canopy that originally contained a statue of George V sculpted after his death in 1936; the statue has since been relocated to a more peripheral location. The Kingsway was intersected by perpendicular axes and by grand diagonal boulevards radiating out from these axes to form a hexagonal network. The overall effect was reminiscent of L'Enfant's plan for Washington, for which Lutyens especially had expressed great admiration. The intersecting nodes of this network contained plazas and important buildings, such as the two churches designed by Henry Alexander Medd: the Cathedral Church of Redemption (1931, the main Anglican church for the British officials) and the Italianate Roman Catholic Church of the Sacred Heart (1934). The boulevards themselves were lined with bungalows, residences derived from the indigenous architecture of Bengal (bungalow is, in fact, an English corruption of the word bangla, meaning "from Bengal"). A typical bungalow was a single-storied horizontal structure with covered verandahs and a high ceiling to keep the interior shaded and cool. The bungalows originally housed British officials and today are home to ministers and other high bureaucrats in the Indian government.

Other prominent buildings of New Delhi include Connaught Place (1934), designed by Robert Tor Russell and named after the king's uncle, the Duke of Connaught. North of Lutyens' and Baker's central plan, this two-story shopping arcade with Palladian arches and stuccoed colonnades is arranged radially in two rings about a central lawn. Russell also designed the Commander-in-Chief's House (1930) south of the Viceroy's House, later the home of Prime Minister Nehru and today a museum.

Lutyens wished to use a purely classical European idiom for the entire design; he was especially open in his aversion to Hindu and Mughal architecture and his disdain for stylistic admixtures. Baker was more open to integrating Indian and European elements. For political reasons, however, Lutyens used Indian motifs in his final designs for many of the buildings; these include the chhajja (stone cornice), chhatri (rooftop cupola), and other decorative detailing. Some critics argue that the use of Indian motifs can hardly qualify as being a true synthesis of traditions, whereas others testify to the harmonious effect created by the mixture.

The British ruled India for only 16 years after the completion of New Delhi, until Independence in 1947. In that time, and in the over 50 years since independence, New Delhi has expanded into new territory in every direction beyond the relatively small City Beautiful envisioned by Lutyens and Baker. The city's population is now estimated at 12 million people; this unprecedented growth is primarily a result of migration first from western Punjab after partition with Pakistan in 1947 and more recently from the entire country. In the process, it has expanded to incorporate Shahjahanabad (now called Old Delhi) and other older cities and villages around it. Lutyens' and Baker's colonial architecture and British urban planning (characterized by low-lying buildings in garden settings with tree-lined avenues) remain mostly intact in what is now called Central Delhi, with some stylistically mixed and high-rise in-fill. The remainder of the city is more diverse in terms of both economic level and style; modern New Delhi encompasses everything from the slum to the gated community, and styles as diverse as European classical, Islamic, Modern, and Postmodern, blended with vernacular traditions from an entire subcontinent.

MANISH CHALANA

Sennott R.S. Encyclopedia of twentieth century architecture,Vol.2 (G-O). Fitzroy Dearborn., 2005. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| GALLERY |

|

| |

|

| |

1970-1982, Sheikh Sarai Housing, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1973-2015, Delhi Television Centre, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1975-1988, CENTRAL INSTITUTE OF

EDUCATIONAL TECHNOLOGY,

New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

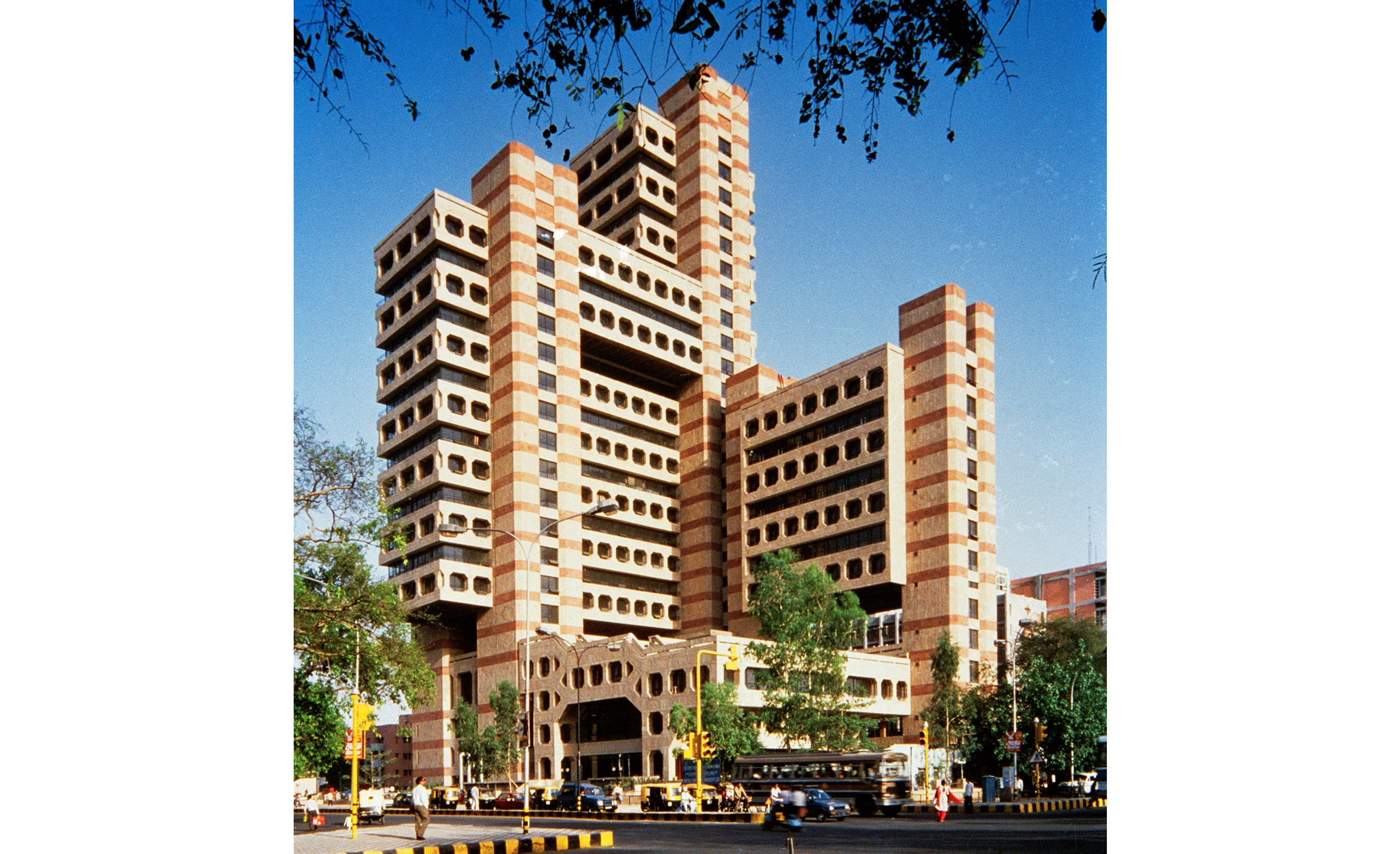

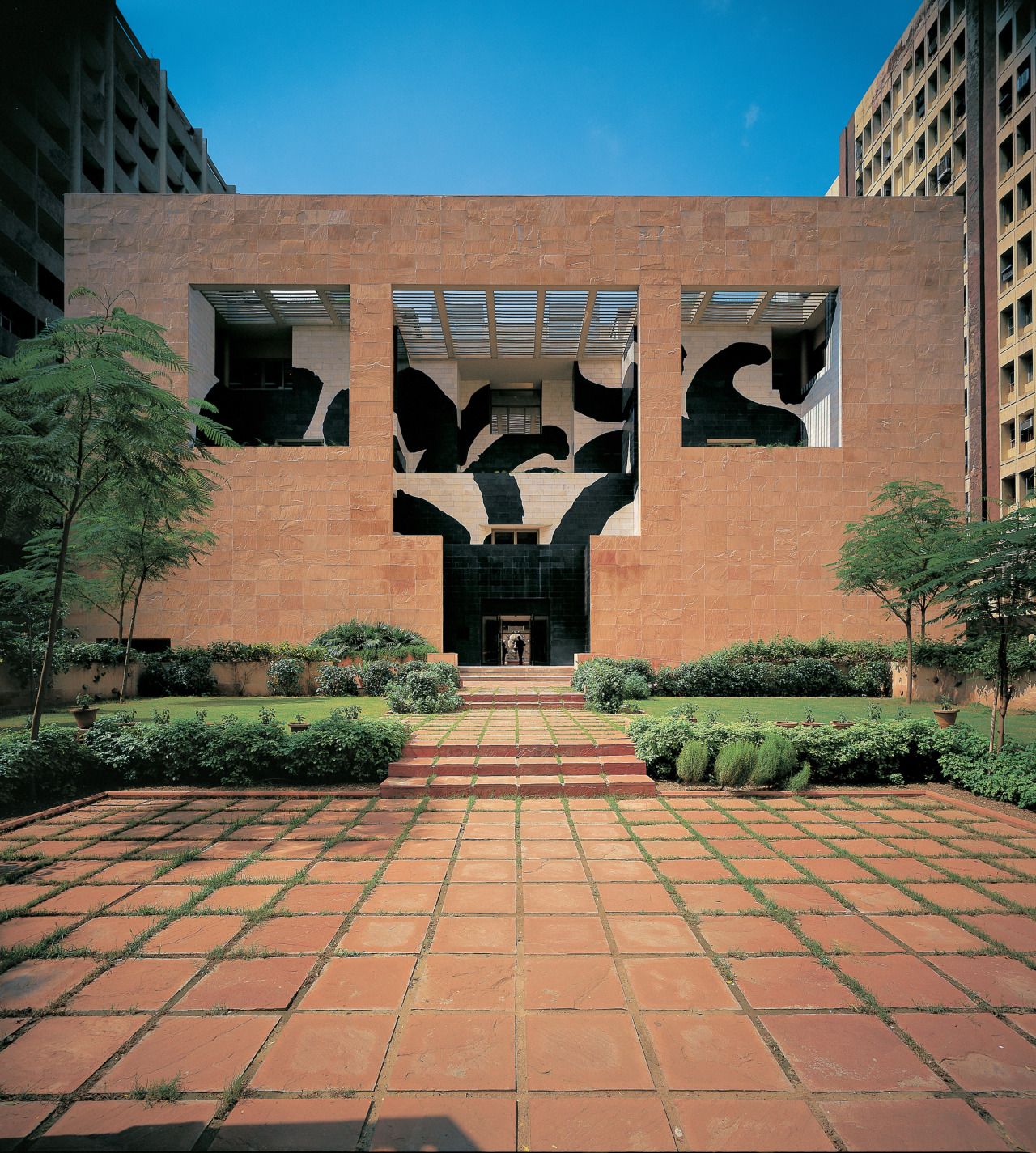

1975-1986, JEEVAN BHARATI, DELHI, INDIA, CHARLES MARK CORREA |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

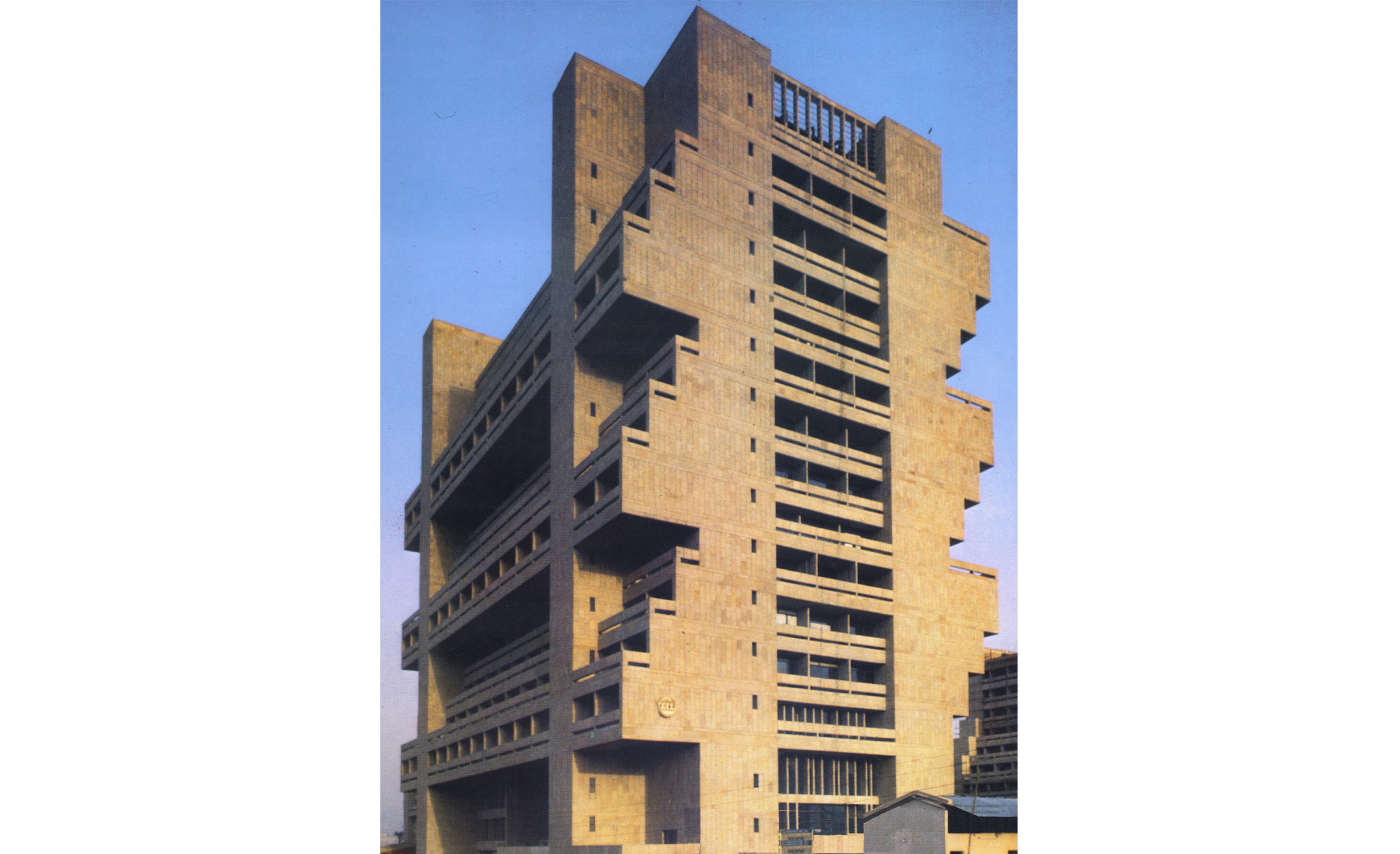

1976-1989, STATE TRADING CORPORATION, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1978-1983, ENGINEERS INDIA HOUSE, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

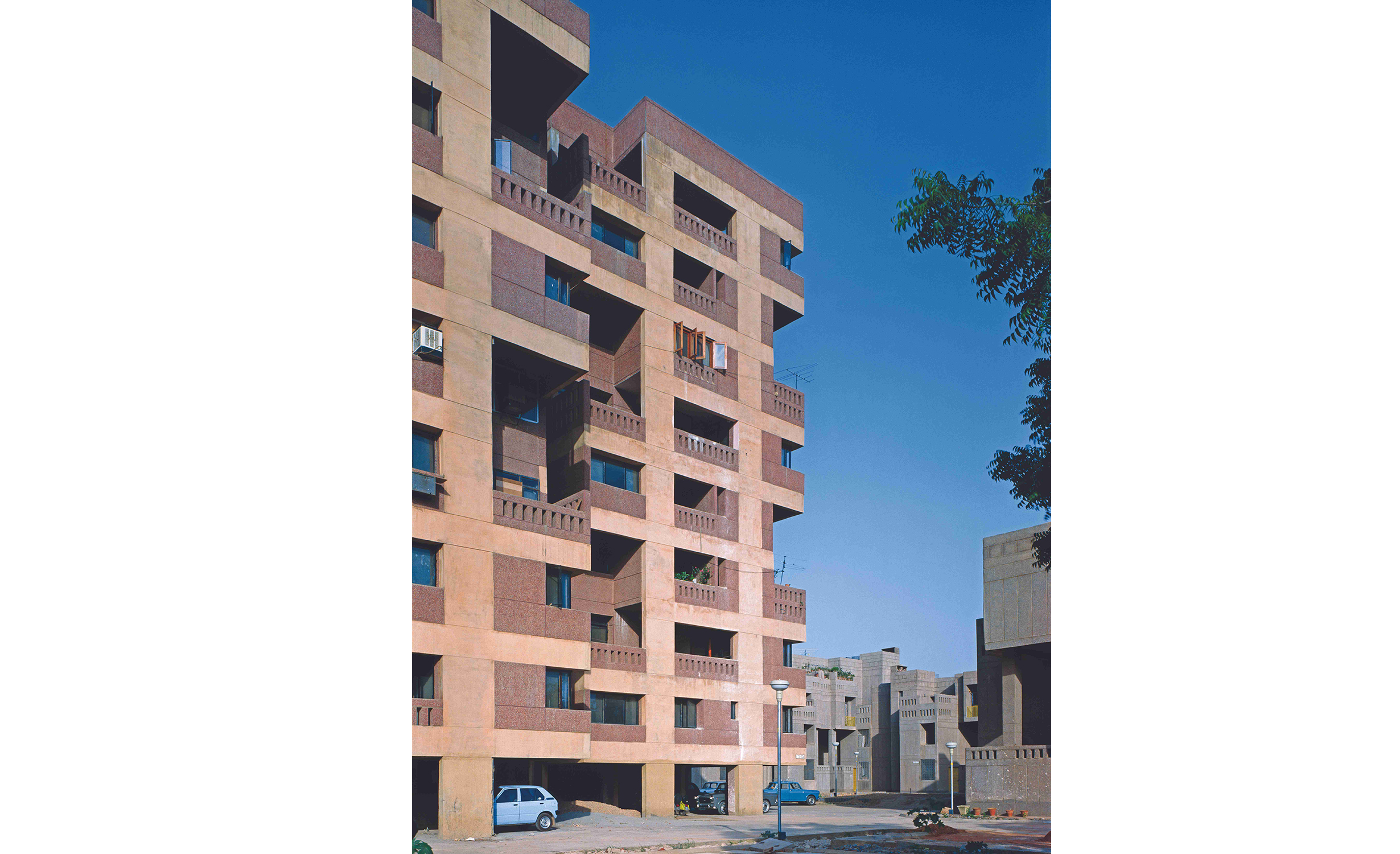

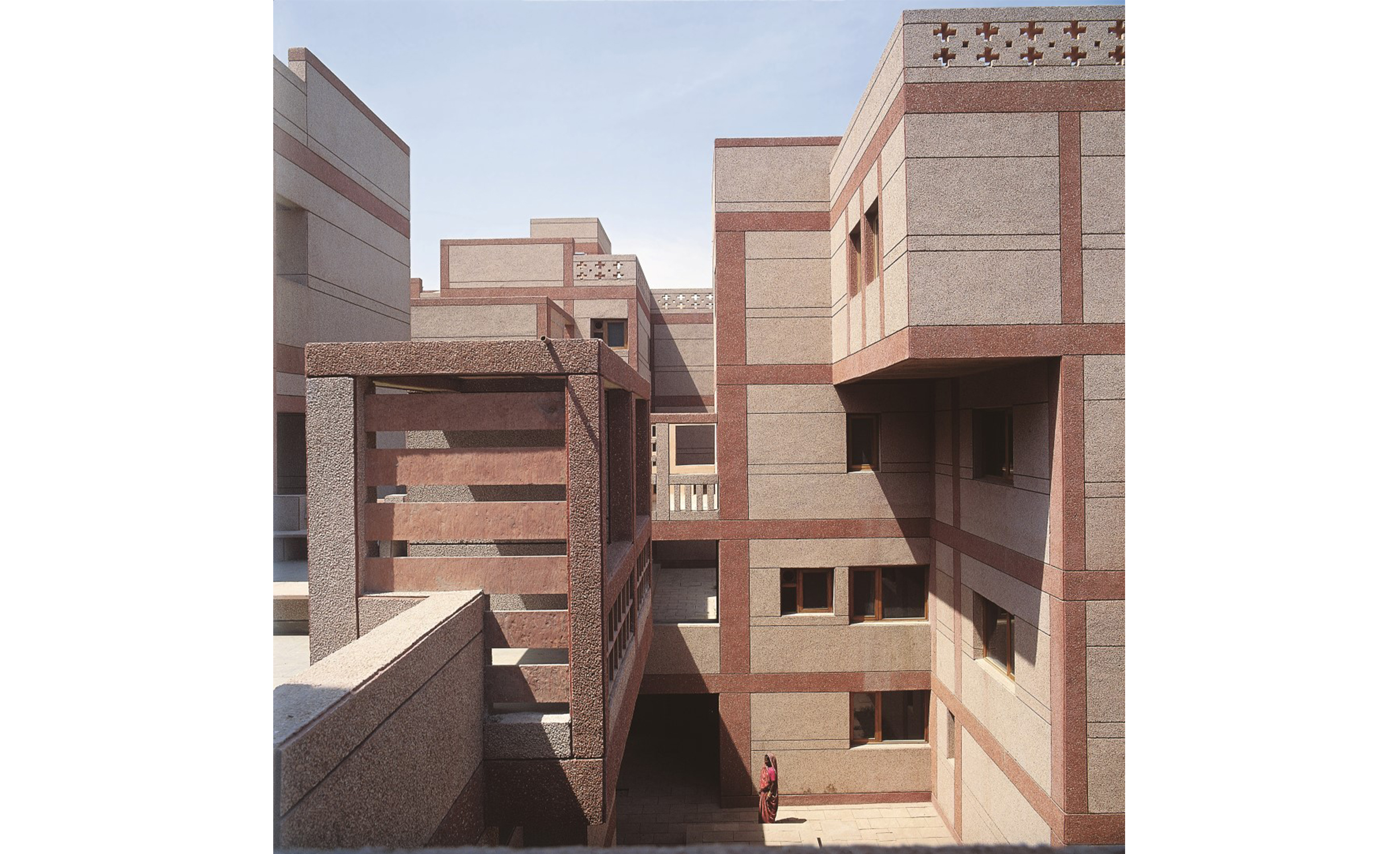

1979-1984, Zakir Hussain Co-operative Housing,

New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1980-1989, SCOPE COMPLEX, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1983-2000, NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF IMMUNOLOGY,

New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1984-1986, Supreme Court Co-Operative Group Housing, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1987-1992, British Council, New Delhi, INDIA, CHARLES MARK CORREA |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1989-1994, NTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR

GENETIC ENGINEERING AND BIOTECHNOLOGY,

New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

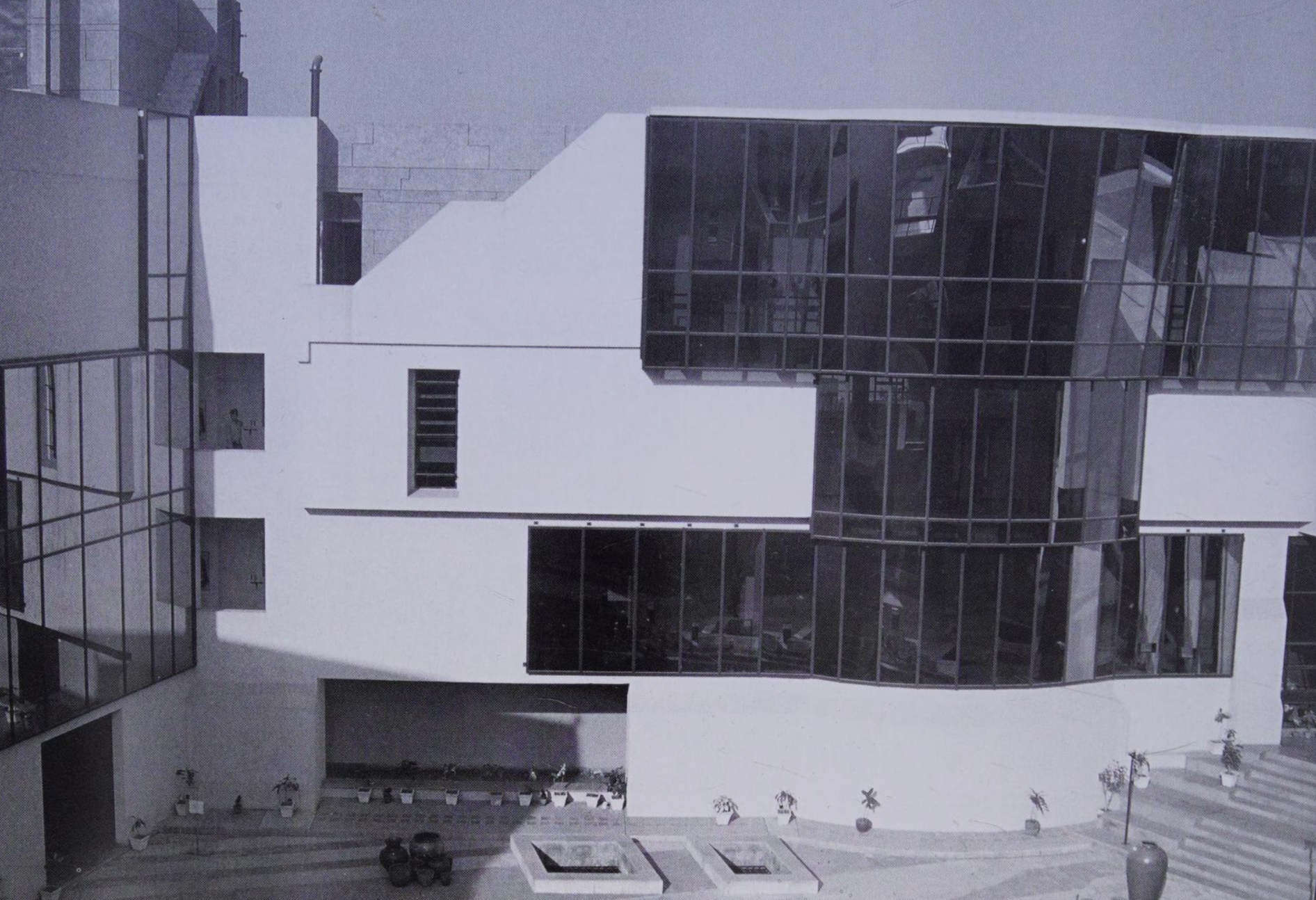

1990-1997, National Institute of Fashion Technology, New Delhi, INDIA, BALKRISHNA V. DOSHI |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

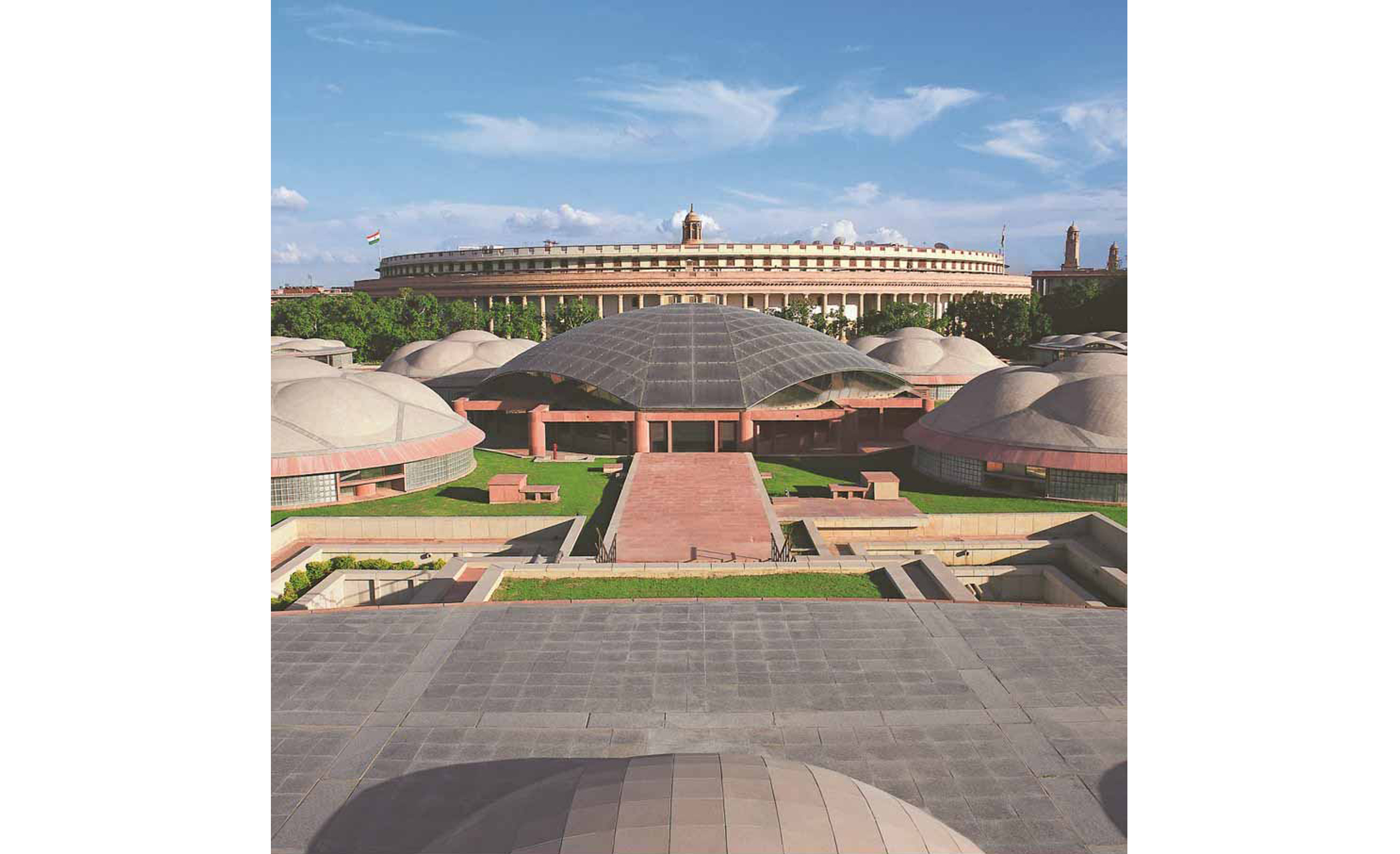

2003, Library for the Indian Parliament, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| ARCHITECTS |

|

| |

REWAL, RAJ |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| BUILDINGS |

|

| |

1970-1982, Sheikh Sarai Housing, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

1973-2015, Delhi Television Centre, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

1975-1988, CENTRAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATIONAL TECHNOLOGY, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

1975-1986, JEEVAN BHARATI, DELHI, INDIA, CHARLES MARK CORREA |

| |

|

| |

1976-1989, STATE TRADING CORPORATION, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

1978-1983, ENGINEERS INDIA HOUSE, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

1979-1984, Zakir Hussain Co-operative Housing, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

1980-1989, SCOPE COMPLEX, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

1983-2000, NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF IMMUNOLOGY, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

1984-1986, Supreme Court Co-Operative Group Housing, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

1984-1986, Supreme Court Co-Operative Group Housing, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

1987-1992, British Council, New Delhi, INDIA, CHARLES MARK CORREA |

| |

|

| |

1989-1994, NTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR GENETIC ENGINEERING AND BIOTECHNOLOGY, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

1990-1997, National Institute of Fashion Technology, New Delhi, INDIA, BALKRISHNA V. DOSHI |

| |

|

| |

2003, Library for the Indian Parliament, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| MORE |

|

| |

INTERNAL LINKS

CHANDIGARH; INDIA;

FUTHER READING

Hall, Peter Geoffrey, Citin of Tomorrow: An Intellectual Histury of

Urban Planning and Design in the Twentieth Century, Oxford,

UK and New York: Blackwell, 1988

Irving, Robert Grant, Indian Summer: Lutyens, Baker, and Imperial

Delhi, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981

|

| |

|

|